I love having lots of homemade olives around but I have to confess that sometimes I’m a bit slack with changing pickling liquid every day. Luckily there’s a method that suits my temperament very well – just chuck the olives and dry salt into a bucket and stir once a week. You don’t have to slit each olive or change the water or anything like that and best of all I think these are my favourite tasting olives too – they are kind of leathery and wrinkly, surprisingly they don’t actually taste all that salty though! Most of the salt draws liquid out of the olives and then runs away. Theres a really noticeable flavour of olive oil that I don’t get from brined olives. The method & equipment I’m using for this years batch is below. I bought 2 large plastic buckets with lids, and drilled holes in the bottom of one. The olives and salt go in the bucket with holes, which sits inside the other bucket to catch the juice. In previous years I’ve used a colander, anything that holds the olives and lets a bit of liquid drain out is fine.

Dry Salt Cured Olives – The method

1. Use bucket (or a large colander, large basket etc) with holes in the bottom so liquid can drain out. I sat a clean tea in the bottom of the olive bucket to stop too much salt falling out. Set the bucket over another bucket or tub to catch the juice.

2. Layer olives with salt in the bucket – about twice the weight of olives to salt. A 20 liter bucket holds up to 10kg olives with 5kg salt. Cover all of the top with a layer of salt.

3. Stir the olives around once a week so that they all contact salt evenly – it’s easiest to empty the outer tub of liquid, tip the olives into it then back into the strainer, and finally add a fresh layer of salt on top.

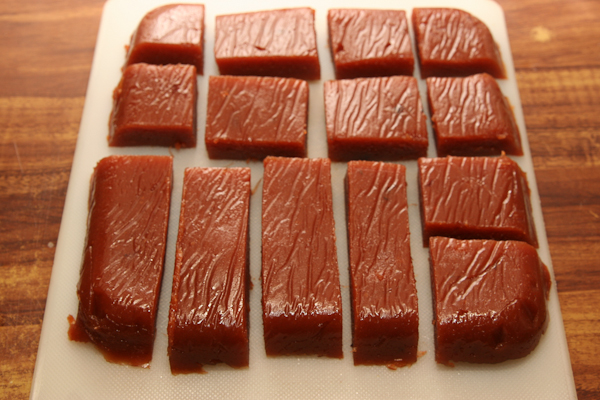

4. After a few weeks, start tasting. Continue the cure until bitterness is gone. This might take from 4-6 weeks, depending on the olives. When they are ready, remove olives from salt – I shook them through a big colander. Then rinse off remaining salt and let them dry.

The cured olives can be stored in a 3% salt brine, or brine+vinegar but I like them best just kept in olive oil in jars or vacuum sealed bags. This year I mixed up chilli, garlic powder, fennel seeds and paprika to marinate the olives that were then vac-packed in serve-sized bags. They keep pretty well but I’ve seen recommendations to freeze them when vac packed to keep them fresh for even longer.